Brief History

You may like to read our ‘Beginner’s Guide‘ if you are new to the S&D.

Before railways, transport was principally by horse-drawn vehicles and canal boats. The key advantage of railways before motor cars was the ability to transport people and particularly goods much more speedily and in bulk over considerable distances.

A navigable waterway had been opened in 1833 from Highbridge, a mile inland from the North Somerset coast on the River Brue, to Glastonbury on the Somerset Levels, using the river in conjunction with a newly-cut canal. Glastonbury was the location of the slipper, shoe and sheepskin rug manufacturers, the brothers Cyrus and James Clark.

They saw the advantage of replacing the canal by a railway, to connect directly with the existing Bristol to Exeter main line at Highbridge. In 1854, the Somerset Central railway line was opened between Glastonbury and Highbridge. With business expansion in mind, in 1858 the railway was extended to from Highbridge to Burnham-on-Sea and in the following year from Glastonbury to Wells.

It was believed that a railway line directly linking the Bristol and English Channels would provide a safer and more rapid transport of goods from South Wales to the South Coast than the treacherous sea route around Land’s End. Consequently, the Somerset Central Railway was extended south-eastwards from Glastonbury to Cole (near Bruton) in 1862.

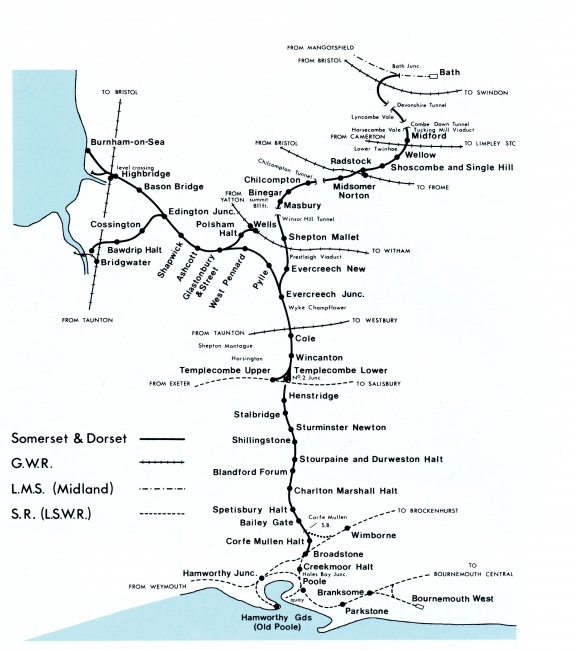

Reproduced by permission of Ian Allan Publishing Ltd from An Historical Survey of the Somerset & Dorset Railway by C. W. Judge and C. R. Potts, Oxford Publishing Co, 1979/1988 and The Somerset Dorset Line From Above: Bath to Evercreech Junction, Kevin Potts, Ian Allan Publishing Ltd, 2013, and The Somerset Dorset Line From Above: Evercreech Junction to Bournemouth, Kevin Potts, Ian Allan Publishing Ltd, 2014

One of the handsome S&D engines on the main line at the end of the nineteenth century. SDRT Collection

In 1860, the Dorset Central Railway company, which shared essentially the same management team as the Somerset Central, opened a railway line between Blandford and Wimborne, where it connected with the Southampton to Dorchester line; and then another between Templecombe and Cole in 1862. In that same year the two companies amalgamated to become the Somerset & Dorset Railway. The missing link between Templecombe and Blandford was opened in 1863, resulting in a coast to coast route between Burnham and Hamworthy in Poole Harbour.Later, a line was opened from Broadstone to Poole in 1872, and on to Bournemouth West station in 1874, which then became the southern terminus for the Somerset & Dorset trains.

The relative lack of business over this rural route resulted in the need for further expansion to achieve financial security. It was decided to extend the line from a junction near the village of Evercreech to Bath, where it would link up with existing railways to Bristol, the Midlands and the North; at Templecombe, it would link up with the route from London Waterloo to Devon and Cornwall. Thus, it would provide a through route from the North and Midlands to the South West.

This line over the Mendip hills was opened in 1874, but had been expensive to build, with steep gradients, and numerous tunnels and viaducts. Together with the sudden volume of traffic which swamped the available rolling stock and track capacity, the Somerset & Dorset Railway was financially broken. In 1875, it was leased to the Midland Railway and the London & South Western Railway. The fragility of the system was underlined in 1876 when 13 people were killed in a head-on collision near Radstock.

The new owners invested in staff training, improved track and signalling, and provided adequate rolling stock and locomotives. In 1885, a new line was opened between Corfe Mullen and Broadstone, which avoided having to reverse trains at Wimborne. The railway had been single-track throughout, with passing places at most stations; during the period 1892-1905, the line between Midford, just south of Bath, and Templecombe was converted to double track, as was the line between Blandford and Corfe Mullen. A branch line was opened between Edington Junction and Bridgwater in 1890. More information about each station is available in the Members’ Area of this website.

Principal traffic was moving freight from the north at Bath to Templecombe for onward destinations; 203,571 wagons were so conveyed in 1910. The Somerset & Dorset system also generated its own traffic – coal from the North Somerset coalfields around Radstock and Midsomer Norton, stone from the Mendip quarries, peat from the Somerset Levels and farm produce and milk from country stations bound for London. Inbound traffic included general provisions, products, and coal for local domestic and industrial use. Parcels and mail were also carried.

Photo: Shepton Mallet – copyright John Woods, SDRT Collection

Photo: Bath Green Park Station at the northern end where S&D trains connected with the Midland Railway. Woods Collection, SDRT.

The golden commercial era that had commenced around 1890 ceased following the First World War. Lorries, now superfluous to the war effort, challenged the railway’s freight business, while buses started to compete for passengers from the late 1920s. Costs were rising but business was not expanding. The line between Corfe Mullen and Wimborne closed to passengers in 1920. In a bid to reduce costs; the workshops at Highbridge, where the line’s rolling stock had been built and locomotives maintained, was closed in 1930. From this date, the Somerset & Dorset ceased to operate as a separate entity, now being managed directly by the London Midland & Scottish Railway and the Southern Railway, the successors of the Midland and London & South Western Railways respectively. The distinctive blue livery for engines and coaches also disappeared.

Passenger traffic was never substantial. It largely consisted of schoolchildren travelling to and from school, a small amount of commuting to work, particularly into Bath and into Bournemouth, housewives travelling to shop and social trips to the larger towns and the seaside. In 1910, a daily express train was introduced between Manchester and Bournemouth which travelled over the Somerset & Dorset. In 1927 it was named ‘Pines Express’, becoming an iconic feature of the line. Other long-distance services were developed in the 1920s and 1930s, running during the summer months. This holiday traffic over the line reached its peak in the late 1950s, when trains for Bournemouth ran on summer Saturdays from places such as Manchester, Liverpool, Bradford, Leeds, Nottingham, Derby and Birmingham.

When Britain’s railways were nationalised in 1948, the Somerset & Dorset network was divided between the Western and Southern Regions of British Railways. Ever-increasing motor car ownership in the 1950s and 1960s led to continuing reductions in passenger usage and, together with declining freight, led to a worsening of the line’s financial position. The section of line between Highbridge and Burnham and the Glastonbury to Wells line closed in 1951 (apart from occasional excursion trains); the Bridgwater branch closed in the following year. In 1963, the Beeching Report recommended the closure of Britain’s loss-making lines, and into this category fell the remainder of the Somerset & Dorset.

A rebuilt Bulleid hauling a nine coach holiday train out of Bath up to Devonshire Tunnel, a heavy load for a single engine for a 1 in 50 climb.© Bob Woolan/Andrew Ford Collection

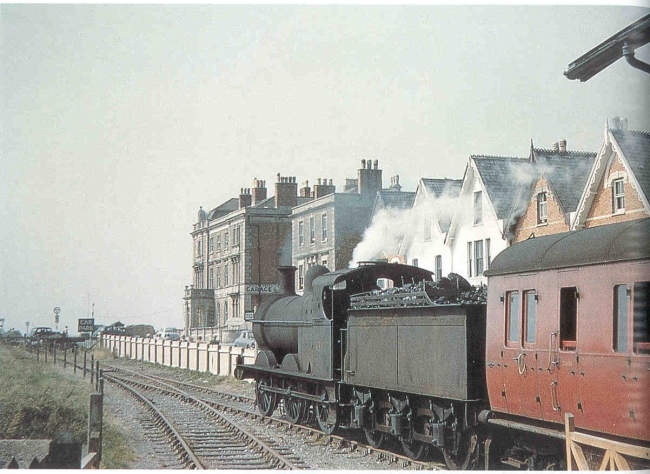

One of the last excursion train arrives at Burnham, the point where connections to South Wales would have completed the original dream of linking Wales to France. SDRT Collection.

Whereas modernisation, including replacing steam locomotives by diesels, was taking place elsewhere on Britain’s railways, this did not extend to the Somerset & Dorset line. Long-distance freight traffic was routed away from the line, as had already happened to the prestigious ‘Pines Express’ and the long-distance Saturday holiday trains from the end of the summer schedules in 1962. It limped along until closure to passengers in March 1966. Some localised freight traffic lingered on, but had ceased by the mid-1970s.

Despite changes of ownership over the years, the Somerset & Dorset retained its own sense of individuality and identity to the last. Even at closure in 1966, the line was operated in essentially the same way as it has done since Victorian times – that was part of its charm.